Entries Tagged as 'Geography'

If you want an idea of how key to Baltimore the Francis Scott Key Bridge is, here are some photos to remind you:

Baltimore Harbor. Note the Francis Scott Key Bridge, above the middle.

On the right is the Francis Scott Key Bridge, also known in its time as the Car Strangled Spanner. It was dropped by the MV Dali container ship. Note that these ships all load and unload on the far side of the bridge at many docking sites. All need to thread the eye of the bridge’s needle.

This view shows the whole span of the bridge, from the north side to the south, across the mouth of the harbor.

Those three are among six I’ve posted on Flickr for the sole purpose of making them useful. Such as now, twelve years after I shot them. Because yesterday an errant cargo ship, the MV Dali, brought the bridge down by taking out the southwest support column (left side in this view) for the central span, killing at least six people and leaving the “Car Strangled Spanner” out of commission for the next few years.

Like all my other public photos, these are Creative Commons licensed to require only attribution. I see this as the infrastructure of public photography supporting the infrastructures of journalism and archivy.*

Photographically, they aren’t great. But they are free, so if you’re writing about the bridge and want an easy photo to use, have at ’em.

*Meaning (if you skip that link) “the discipline of archives.” For the practice of creating and maintaining archives, I prefer archivery, and would have used it here if a search for that word hadn’t suggested archivy instead.

Tags: Building · Emergency · Geography · Industry · Media · Photography · Roads/Bridges · Travel · Water

“American vs. Canadian Radio” — drawn by bing.com/images/create

A couple of years ago I was asked on Quora, “How do American radio stations compare to Canadian stations?” This was my answer.

Mostly the differences are regulatory. But some are also geographic. Examples:

- The Canadian government has a national network, the CBC, much as does the U.K. with the BBC. And, like the BBC, it’s very reputable. Both are “royal” entities, for which there is no U.S. equivalent. (And no, NPR doesn’t qualify, since it’s independent of the federal government and almost entirely—last report, 98+%—paid for by member stations, sponsorships and underwriting.)

- Programming is more highly regulated, especially around music, in Canada. For example, the Canadian Radio-Televsion and Communmicatons Commission (CRTC) has Canadian content requirements for music on Canadian radio, which requires that commercial, community, campus and native radio stations “must ensure that at least 35% of the Popular Music they broadcast each week is Canadian content.” The percentage for CBC stations is 50%.

- The CRTC is committed to sunsetting AM broadcasting, while the FCC is not. While there are still some CBC stations still on the AM band, many signals have either gone dark or have been sold off. Here is a list of the remaining CBC AM signals.

Despite Canada’s slow rollback of AM broadcasting, its prairie features an AM station with the largest daytime* coverage in the world: CBK/540 in Watrous, Saskatchewan. While there are lots of 50,000-watt stations in the world (and that’s the max allowed in the U.S. and Canada)—and a handful cranking out up to two million watts—CBK’s 50,000-watt transmitter sits on some of the most conductive dirt in the world, giving the station coverage that reaches from the Rockies in Alberta to the west, the shores of Hudson Bay to the east; and north across the borders of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and well into Montana, North Dakota, and Minnesota to the south:

One of those two million-watt giants is Transmitter Solt, for Kossuth Rádió, Hungary’s national radio station. While its signal is immense electronically, its daytime* coverage, while very large, is limited by relatively nonconductive ground. Still, in a way, Transmitter Solt is also Canadian, since the transmitter itself is made by Nautel, of Nova Scotia, which in recent years has become what some regard as the preeminent maker of broadcast transmitters.

______________________

*Note that coverage by day and night is vastly different for AM (aka MW) radio. That’s because in daytime the lowest (D) layer of the ionosphere absorbs signals in that band, and at night the same signals bounce off the next layer up (E) for distances typically of several hundred miles. Or, in cases like Transmitter Solt, thousands of miles. As a somewhat separate matter, shortwave signals bounce off the higher F1 and F2 layers. Check that last link for particulars.

Tags: Broadcasting · Geography · Radio

Joshua trees shot in pano mode by a phone in a moving car.

I’m making lemonade here. The lemon is erroneously putting an album of photos shot at Joshua Tree National Park into my Flickr site devoted to infrastructure rather than the one for everything else. The lemonade is giving this blog some juice in the form of a useful topic: absence of infrastructure. There is a lot of that in the world, and this park is an okay example.

I say okay because it’s not Antarctica, the middle of the ocean, or the Taklamakan. There is a paved road, on which tantalized visitors can gaze through car windows before they hike off on foot to look at wildlife, climb rocks, and enjoy other adventures. There is also some cell coverage, even though the park says there is none. We could get online most of the way to the Wall Street Stamp Mill ruins. Two days earlier we took a hike to Barker Dam, which also featured a bit of cell coverage.

Just off the trail nearby are the remains of a windpump style windmill, that supplied water for the mill and the ranches nearby. Not sure what anyone ranched there, but the windpump made a degree of civilization possible. And I suppose that’s what infrastructure is: a minimum requirement for the kind of life we call civilized.

Thoughts welcome.

Tags: Building · Discovery · Geography · History · Mining · Photography · Rural · Travel · Water

Mountains are temporary. All are in the queue for demolition, eventually. So is the whole planet. I explain that in The Universe is a Startup.

Blogs are more like beach sand. Or a whiteboard. So is the whole Web. In the old days we thought it was a library. Now we know it’s not. (Though the Internet Archive truly is, and that’s why we love it.)

On Saturday this blog and the one behind that first link—my personal one, which I’ve had at blogs.harvard.edu since 2007, will be gone from that domain. So will ProjectVRM, which I started at the Berkman Klein Center in 2006, and remains very active.

The challenge now is to migrate them to new domains.

Those qualify as infrastructure too. While they last.

Tags: Geography · History · Industry

To answer the question Where are SiriusXM radio stations broadcasted from?, I replied,

If you’re wondering where they transmit from, it’s a mix.

SiriusXM transmits primarily from a number of satellites placed in geostationary orbit, 35,786 kilometres or 22,236 miles above the equator. From Earth they appear to be stationary. Two of the XM satellites, for example, are at 82° and 115° West. That’s roughly aligned with Cincinnati and Las Vegas, though the satellites are actually directly above points along the equator in the Pacific Ocean. To appear stationary in the sky, they must travel in orbit around the Earth at speeds that look like this:

- 3.07 kilometres or 1.91 miles per second

- 110,52 kilometres or 6,876 miles per hour

- 265,248 kilometres or 165,025 miles per day

Earlier Sirius satellites flew long elliptical geosynchronous orbits on the “tundra“ model, taking turns diving low across North America and out into space again.

Satellites are also supplemented by ground repeaters. If you are in or near a site with repeaters, your Sirius or XM radio may be tuned to either or both a transmitter in space or one on the ground nearby. See DogstarRadio.com’s Satellite and Repeater Map to see if there is one near you.

In addition, SiriusXM also streams over the Internet. You can subscribe to radio, streaming or both.

As for studios, those are in central corporate locations; but these days, thanks to COVID-19, many shows are produced at hosts’ homes. Such is the case, for example, with SiriusXM’s popular Howard Stern show.

So, to sum up, you might say SiriusXM’s channels and shows are broadcast from everywhere.

I should add that I’ve been a SiriusXM subscriber almost from the start (with Sirius), and have owned two Sirius radios. The last one I used only once, in August of 2017, when my son and I drove a rental minivan from Santa Barbara to Love Ranch in central Wyoming to watch the solar eclipse. After that it went into a box. I still listen a lot to SiriusXM, almost entirely on the phone app. The rest of my listening is over the Web, logged in through a browser.

Item: a few days ago I discovered that a large bill from SiriusXM was due to a subscription for both the radio and the Internet stream. So I called in and canceled the radio. The subscription got a lot cheaper.

I bring this up because I think SiriusXM is an interesting one-company example of a transition going on within the infrastructure of what we used to call radio and would instead call streaming if we started from scratch today.

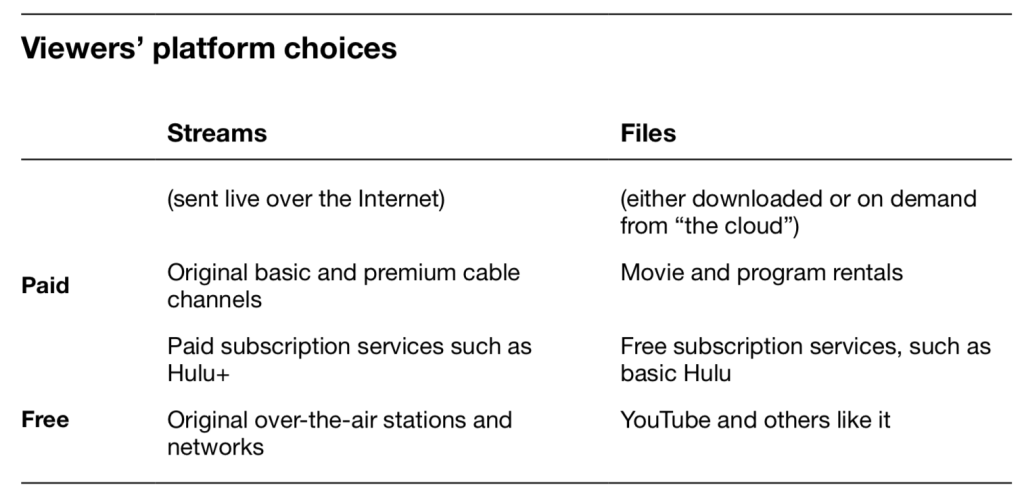

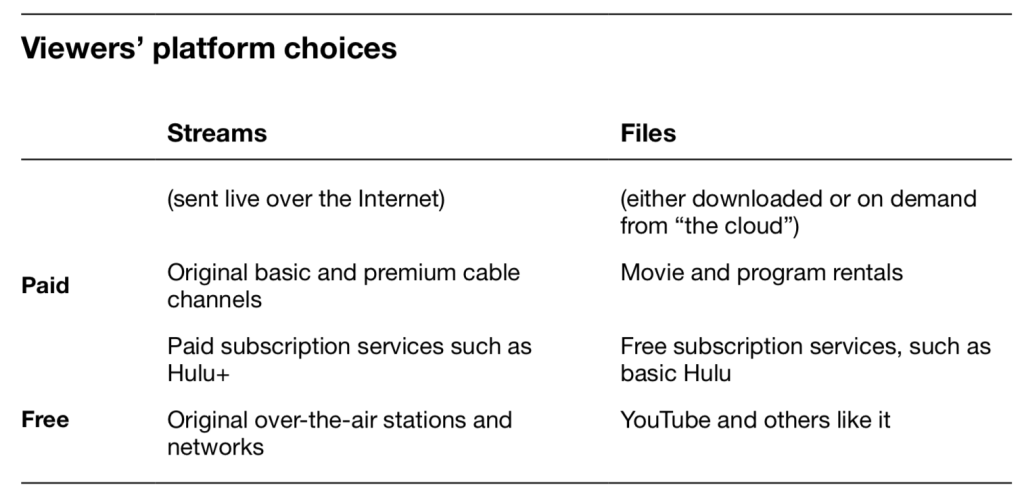

In The Intention Economy (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012), I saw this future for what we wouldn’t call television if we were starting from scratch today (or even when this was published, eight years ago):

Today we’d put Netflix, Amazon Prime, YouTube TV and Apple TV in the upper left (along with legacy premium cable staples, such as HBO and Showtime). We’d put PBS stations there too, since those became subscription services after the digital transition in 2008 and subsequent spectrum sales, which reduced over-the-air TV to a way for stations to maintain their must-carry status on cable systems. (Multiple “repacks” of TV stations on new non-auctioned spectra have required frequent “re-scans” of signals on TVs of people who have antennas and still want to watch TV the old-fashioned way.)

Over-the-air radio is slower to die, but the sad fact is that it has been terminal for years. Here’s the diagnosis I published in 2016. I’ve also been keeping a photographic chronicle of radio in hospice, over on my Flickr account for Infrastructure. A touching example of one station’s demise is Abandoned America’s post on the forgotten but (then) still extant studios of WFBR (1924-1990) in Baltimore.

Like so much else, over-the-air radio is being subsumed into Internet streams and podcasts (in the two Free quadrants above).

Want to have some fun? Go to RadioGarden and look around the globe at streams from everywhere. My own current fave is little CJUC in Whitehorse, Yukon. (I list many others from earlier explorations here.) All of those are what we call “on” the Internet. But where is that?

We can pinpoint sources, as RadioGarden does, on a globe, but the Internet defies prepositions, because there is no “there” there. There is only here, where we are now, in this non-place, a functionally vast but geographically absent non-place: a giant zero with no distance and no gravity because its nature is to defy both. I’m in Santa Barbara right now, but could be anywhere. So could you.

On the Internet, over-the-air TV and radio are anachronisms, though charming ones. Like right now, as I’m listening to Capricorn FM from Polokwane, South Africa. (“Crazy up-tempo hip-hop” is the fare.) But I’m not listening on a radio, which would need to tune in 89.9fm, within range of the transmitter there. I’m here, on (or in, or through, or pick-your-preposition) the Internet.

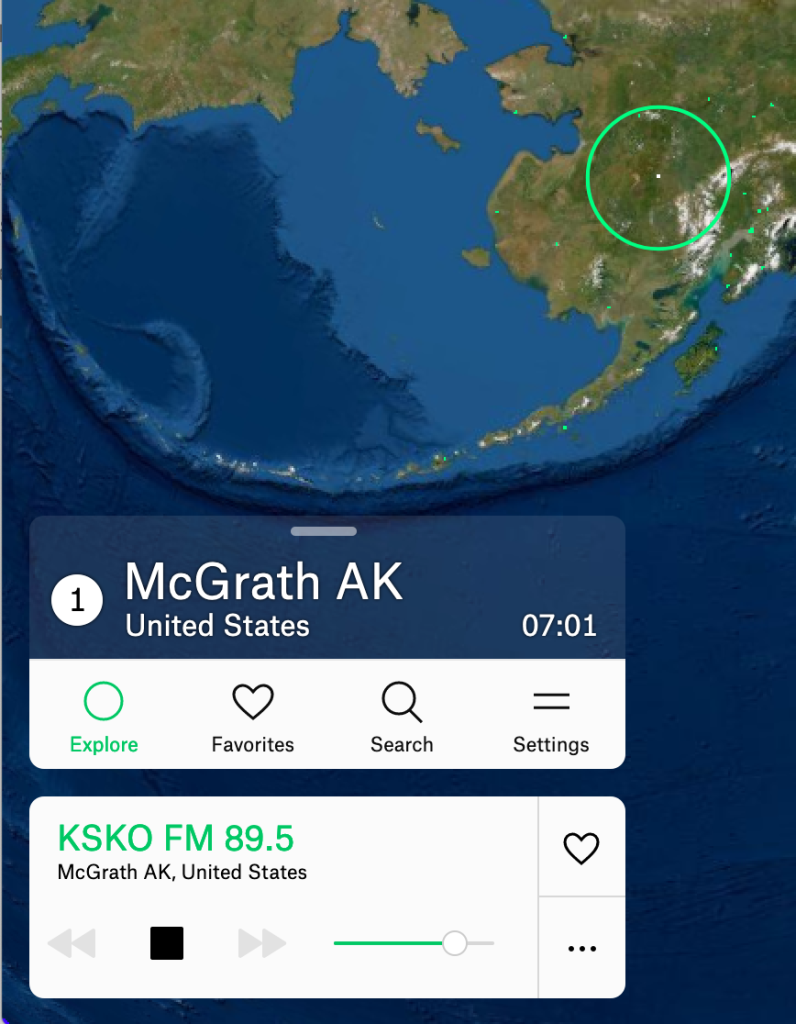

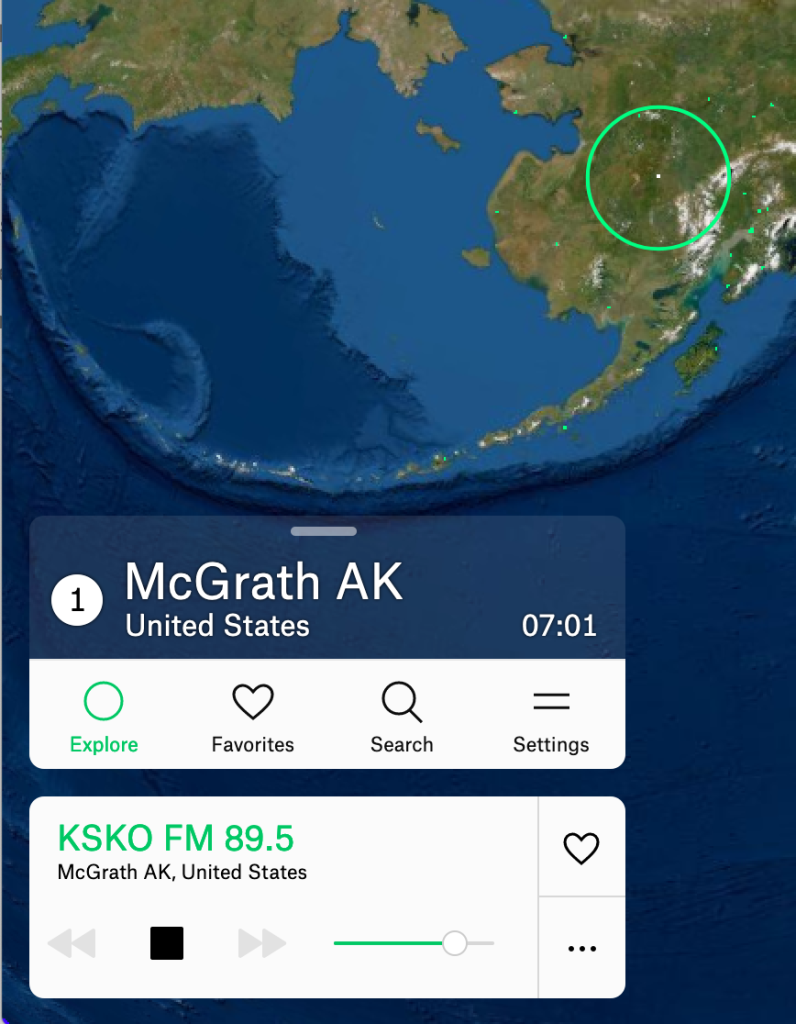

Or consider the case of KSKO/89.5 in McGrath, Alaska, population 319. Here’s how it looks on Radio.Garden:

Geographically, McGrath elongates the meaning of “isolated.” No roads lead there from elsewhere. Visitors come and go to other parts of the world by plane, dogsled, or boat during months when the Kuskokwim River isn’t frozen. (The name is derived from the Yup’ik words for “big slow moving thing.”) In Coming Into the Country, the best book ever written about Alaska, John McPhee says “If anyone could figure out how to steal Italy, Alaska would be the place to hid it.” Power-wise, KSKO is just 90 watts, with an antenna on a pole beside the station. Since the population of McGrath is just 319, and nearly all are within shouting distance of each other, it doesn’t need to be bigger.

What matters, however, is that I’m listening to KSKO right now in Santa Barbara. (Before that I was digging the equally community-involved KIYU in Galena, 130 miles away, where the station a few minutes ago reported a temperature of -30°f. With “freezing icy fog” coming, a high of -15°f and a low tonight of -40°f. Fun.)

A few years ago my teenage son asked me what the point of “range” and “coverage” was for radio stations. Why, he wondered, was it a feature rather than a bug that radio stations’ signals faded away as you drove out of town? His frame of reference, of course, was the Internet. Not the terrestrial world where distance and the inverse square law apply.

Of course, we’ll always live in the terrestrial world. The Internet may go away, or get fractured into regions so telecom companies can bill for crossing borders and not just for use, or so governments can limit what can happen in their regions (as we already have in some countries, most notably China). But the Internet is also an infrastructural genie that is not going back in the bottle. And it is granting many wishes, all in a new here.

Tags: Geography · History · Media · Radio · Television