The towers transmitting the directional signals of AM stations WMCA/570 and WNYC/820. Both are aimed toward New York City from a site alongside the east spur of the New Jersey Turnpike.

I’ve been enjoying The Divided Dial, an On the Media NPR series hosted by Katie Thornton. And, as an old radio guy who knows a bit about how radio waves work, I felt the need to share a correction today when I heard Katie say AM waves come from the tops of towers. So I just posted this through her comment form (adding a couple of links):

Hi Katie. Love the Divided Dial series. One small edit: AM signals do not come from the tops of towers. The waves are so long at AM’s low frequencies that the best way to transmit is using whole towers. In older antenna systems (such as the kind on the FCC’s official seal), the antenna is a vertical wire suspended from what’s called a “hammock,” “bedspring” or “clothesline” between the tops of two towers. That was an early approach that used the horizontal wires between the tops of the two towers to extend the electrical length of the vertical wire between them. But once the bases of towers could be insulated from the ground (thanks to advances in ceramics), and building very tall towers became practical, that approach was abandoned. Most AM stations are also directional. Where you see collections of towers of equal height in a row, a triangle, or a grid, those are AM stations. With their much shorter wavelengths (about as long as outstretched arms), FM antennas can be small. And, since signals go not far past the horizon, FM antennas tend to be mounted atop towers, mountains, and tall buildings. Same with TV. For wi-fi and cellular transmission, frequencies are very high, and antennas are small enough to fit inside or on the edges of small and portable devices. Ever notice the lines that seem to have no purpose dividing sections of the edges of your iPhone? Those are insulators between antennas that are also the edges of the phone’s case. Cheers, Doc

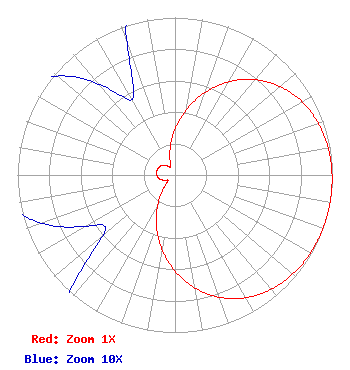

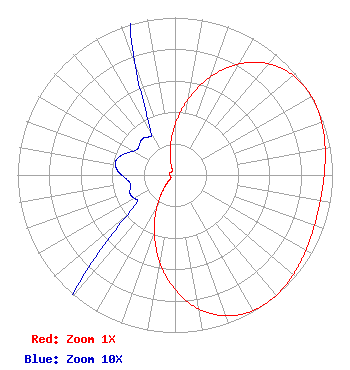

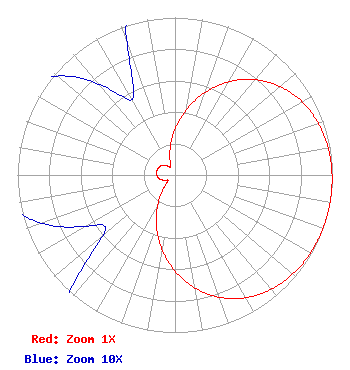

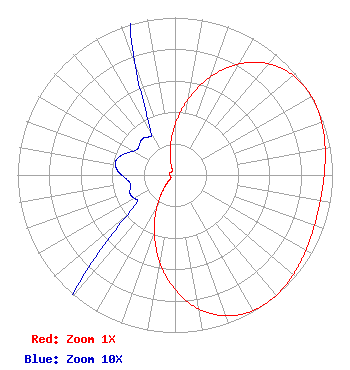

The photo above is from an album I shot when visiting the transmitter site of WMCA and WNYC. The three towers together create directional patterns for both stations. Built by the Truscon Steel Company in 1940, they are some of the oldest broadcasting towers still in use. WMCA’s pattern is the same day and night, and looks like this:

WNYC’s is different day and night, and look like this:

WMCA is 5000 watts full time, and WNYC is 10000 watts by day and 1000 watts by night.

Ground conductivity also affects coverage. The most conductive ground is salt water, and the least conductive is hard bedrock and glacial debris, such as what comprise New York’s boroughs and Long Island. This is why WMCA’s actual coverage looks something like this (courtesy of RadioLocator.com).

That blue line encompasses Bermuda. In its top 40 glory days, WMCA got occasional daytime requests from there. Note that ground conductivity varies a great deal. The best ground conductivity is across sea water, which is why WMCA does so well on the Atlantic and up Long Island Sound. The worst ground conductivity in the US is Long Island, as you can see. It’s also bad across Connecticut and western Massachusetts. In WMCA’s top forty heyday, in the early 1960s, it had daytime listeners in Bermuda, almost 800 miles away. (Not touching nighttime skywave in this post. I’d rather open one can of words at a time.)

Stations with the lowest frequencies on the AM band also have the longest waves, which also travel best along the ground. This is why WNAX, in Yankton, South Dakota, on the same channel as WMCA and also 5000 watts, has daytime coverage that looks like this:

The ground conductivity in prairie states is some of the highest in the country. When my mother was growing up in Napoleon, North Dakota, her family’s favorite local station was WNAX, which was 280 miles away.

The main differences between WMCA and WNAX are ground conductivity and tower length. The ground in prairie states is the most conductive on Earth—technically, 30 mhos/m—while the ground in Long Island is just 0.5 mhos/m. WNAX’s day tower is also unusually tall. At 911 feet, it is more than a half wavelength, making for maximally efficient groundwaves. WMCA’s towers are 336 feet tall: less than a quarter wavelength, and much less efficient.

If we were to invent radio today, we wouldn’t have AM at all. We also might not have FM. Or even radio, since what one might find on a limited number of available signals (from things called “stations”) using a single-purpose device called a “radio” has little audience appeal now that everyone has a phone that can access a zillion sources of information and entertainment anywhere there are cellular or Wi-Fi connections to the Internet.

Still, while radio is still around, it helps to know something about how it works. Hopefully, this post is close to right. I invite corrections. Thanks.

Tags: Broadcasting · Radio

Discarded analog televisions, shot by a Cambridge, Massachusetts sidewalk on November 23, 2010.

This is my column for the July 2008 issue of Linux Journal, titled What happens after TV’s mainframe era ends next February? It presents a good cross-section of wisdom about the “digital transition” of broadcast (over-the-air, or OTA) television from analog to digital transmission, just before it happened.

Remember television? For most of its history, TV wasn’t cable, satellite or YouTube. It was radio with low-res moving pictures. On the transmitting side it was an extension of radio, with transmitters on towers, mountains and high buildings, serving viewers with signals within a range limited by frequency and terrain. Like FM radio, TV was on VHF bands. In the U.S., channels 2-6 were spread from 54 to 88MHz (ending just below the FM band) and channels 7-13 ran from 174-216Mhz.

Not all TV signals are the same. For a signal with a given power and antenna height, range varies with frequency. Higher frequencies have less bending properties than lower ones. Energy is also more quickly absorbed by atmosphere and reduced or halted by buildings and terrain. This is why (again in the U.S.) visual signals for channels 2-6 had maximum powers of 100,000 watts, while those from 7-13 had “equivalent” maximum powers of 316,000 watts.

Range for a given power became more critical when TV expanded to the UHF band in the 1950s. UHF was problematic from the beginning. Receiving it required a new or expanded tuner, plus a new kind of antenna specially designed for the very short UHF waves. This is why TVs from the 50s to the 90s came with little “loop” or “bowtie” antennas, in addition to rabbit ears. The latter were for UHF while the former were for VHF.

For TV stations and networks, VHF channels were much more desirable than UHF ones — not just because VHF channel numbers were lower and more easily remembered, but because UHF signals had much less range than VHF ones. To compete with VHF signals, UHF stations could operate with a maximum power of 5,000,000 watts. And even those signals were never equivalent. If you’re looking to push signals out past the horizon, VHF is much better than UHF.

In recent years the UHF band has also become more cramped. UHF TV originally ran from channels 14-80 (470-894Mhz). Since then everything upwards of channel 51 (698-869MHz) has been lopped off for a variety of other uses. Pagers use the 806-824MHz band (formerly TV channels 70-72). Analog mobile phones got 824–849 MHz (formerly TV channels 73-77). Public safety got the 849-869MHz band (formerly TV channels 77-80). And the “700MHz” band (formerly TV channels 52-69) was auctioned off in March of this year.

Yet UHF is winning, by federal mandate. On February 17, 2009, all U.S. television stations will be required to switch off their analog transmitters and use digital transmission exclusively. Nearly all of that will happen on what’s left of the UHF band. Most stations will maintain their old channel branding, and still be known as “Channel 2” or “Channel 12”, but their signals will in nearly all cases be coming in on a new UHF channel. For example, WNBC-TV in New York will move from Channel 4 to Channel 28. WABC-TV will move from Channel 7 to Channel 45. Both are already broadcasting on those channels in digital form. Come next February, all of them will, even if all they’re doing is putting out low-def pictures over a high-def signal. In the Boston area, where I live most of the year, only one of the four major commercial networks broadcast their evening news in HD. The rest put SD (standard def) pictures on an HD signal.

If you have an HDTV and live within sight of New York TV station transmitters on the Empire State Building, you can probably pick them up over an antenna on your set or your roof. In fact, a loop or bowtie antenna will do. So will length of wire about 5 inches long, attached to the center conductor of your coaxial connection on the back of your set.

But if you live farther away, good luck. Your old VHF TV station not only won’t have the range it did on VHF, but will probably not have the same range as an old analog signal on the same UHF frequency. It certainly won’t have the same behavior. The signals tend to be either there or not-there. They don’t degrade gracefully with increasing “snow”, as analog signals did. They break up into a plaid-like pattern, or disappear entirely. Read through the photo essays here and here for more about how that works, and what a confusing mess this move is making out of the familiar old local channel rosters. Adding to that confusion is the persistence of some DTV stations on the VHF band. Many more stations are applying for VHF channels, because they know the signals will be better, and in most cases will stay on familiar channels. When I look at FCC data for Los Angeles, San Diego, Washington and New York, I see lots of new activity by stations trying to keep their VHF signals. (When looking at that data, note that LIC is for license, APP is for application, CP is for construction permit, CP-MOD is for CP modification and DT after a channel indicates a digital signal.)

While the Program and System Information Protocol (PSIP) will cause stations to publish (and display) whatever channel they choose on the receiving set, the fact remains that most will still radiate on channels other than those they have long been associated with.

Digital signal transmission is also very different from the analog sort. For a variety of arcane technical reasons, many (perhaps most) digital signals are directional. That is, they operate at their full licensed power in only a few (or perhaps only one) direction, and have big dents or “nulls” in other directions. In the old analog days directionality was the exception rather than the rule, and was usually intentional, to protect other signals on the same or adjacent frequencies, or to pull back on the signal in the direction of a mountain that might cause unwanted reflections or places (such as the sea) where nobody lived anyway. Not the case with DTV. Lots of new DTV signals are directional just anyway.

It’s interesting to see how this plays out where we live in Santa Barbara (and where I’m writing this now).

On my old roof antenna and its rotator, I got just about every analog TV station between Santa Barbara and San Diego. That included both VHF and UHF signals. With that antenna (the top one from Radio Shack) I even got little K35DG, a low-power UHF station at UC San Diego with a signal that puts a deep null in our direction (west-northwest, nearly 200 miles across the Pacific ocean). I sent them emails reporting reception and they were amazed.

In our new house (next door to the old one with the big roof antenna) I anticipated the digital switchover and installed a very high-gain Winegard HD-9032 UHF antenna. (Here’s a pdf.) It’s an outstanding device that’s even better on UHF than the old all-channel one. For analog reception it got every UHF in Santa Barbara, Los Angeles and San Diego/Tijuana. In nearly all weather, at nearly all times of year. But that’s analog. What about digital?

For DTV, the Winegard does the best it can, but it’s not enough. The slight terrain shadowing between here and Broadcast Peak (where out local TV stations come from) makes them almost impossible to receive. KEYT on Channel 3 was (and for now still is) a powerhouse that we could get with rabbit ears. KEYT’s digital signal on Channel 27 is barely there. In fact it’s so bad that the one time I got it the signal didn’t stay visible long enough for me to shoot a picture of it. Meanwhile we get nothing from anywhere but the only place that provides a fairly clear signal path, even if it’s across the curved ocean. That’s San Diego/Tijuana. All our HD viewing of over-the-air TV is from there. At one time or another we’ve been able to get all the HD signals from there, and add them into the memory of our Dish Network box, which also has an HD receiver. As you see here and here, the reception is either perfect or screwed. It’s the latter most of the time. Fact is, we’re lucky to get anything at all. Such is the nature of the new system.

My points:

- For many viewers, the digital signals aren’t going to be there, no matter what the viewer does (other than hunt them down on cable or satellite).

- The stations themselves in most cases are giving up viewers, including (as in WECT’s case — see below) whole regional markets.

It’s all a big new game of hard-to-get.

The official response to the hard-to-get problem comes in the form of propaganda. If you watch TV at all you have probably seen many reassuring messages about what’s going to happen in February. If all your watching is on cable or satellite, you won’t notice the difference. But if you watch over the air, the difference will possibly be huge, regardless of what the promotional messages say. So will the disconnect between the whole concept of television and its origins as a live terrestrial medium, with range as a limiting and defining factor. Hey, what’s the “range” of a YouTube video? Or of anything you send over the Net, including live video streams?

Meanwhile, the propaganda persists. Take the DTV.gov site. It begins, “On February 17, 2009 all full-power broadcast television stations in the United States will stop broadcasting on analog airwaves and begin broadcasting only in digital. Digital broadcasting will allow stations to offer improved picture and sound quality and additional channels. Find out more about whether or not you will be impacted by the digital TV (DTV) transition. Go now.” Go there and you’ll find a section that begins “Analog TVs Will Need Additional Equipment to Receive Over-the-air Television When the DTV Transition Ends“, followed by a Converter Box Coupon Program that rewards getting a converter box. Among the top links there is this one to Wilmington, NC – First in Digital.

Turns out Wilmington will be “First in Flight – First in Digital“, making its own conversion early: at 12 noon on September 8, 2008. The press release reads,

Washington, DC — Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Kevin Martin today announced Wilmington, North Carolina, will be the first market to test the transition to digital television (DTV) in advance of the nationwide transition to DTV on February17, 2009. The commercial broadcasters serving the Wilmington television market have voluntarily agreed to turn off their analog signals at noon on September 8, 2008. Beginning at 12:00 pm on September 8, 2008, these local stations, WWAY (ABC), WSFX-TV (FOX), WECT (NBC), WILM-LP (CBS), and W51CW (TrinityBroadcasting) will broadcast only digital signals to their viewers in the five North Carolina counties that comprise this television market.

…This test market will be an early transition that will give broadcasters and consumers a chance to experience in advance the upcoming DTV transition. The Commission is coordinating with local officials and community groups to accelerate and broaden consumer education outreach efforts. The outreach will focus on the special transition date for Wilmington and the steps viewers may need to take to be ready by September.

Okay, let’s take the case of WECT, which has been on Channel 6 for the duration. WECT is sort-of-famously one of the first stations in North Carolina to broadcast from a 2000-foot tower. Here’s what Wikipedia currently says about it:

WECT TV6 Tower is a 2000 ft (609.6 m) tall mast used as antenna for FM– and TV–broadcasting. It was built in 1969 and is situated at Colly Township, North Carolina, USA at 34°34’44.0″ N and 78°26’12.0″ W. WECT TV6 Tower is, along with several other masts, the seventh tallest man-made structure ever created; it is not only the tallest structure in North Carolina, but also the tallest in the United States east of the Mississippi River.

The WECT tower in Colly Township is halfway between Wilmington and Fayetteville,. The latter is a bigger city than Wilmington, which is why WECT’s builders put it there. The WECT analog signal on Channel 6 is huge, and local to both Fayetteville and Wilmington. Back when I lived in North Carolina, north of Chapel Hill, we could get it with my roof antenna any time, even though it was well over 100 miles away. And the audio was always audible just below the bottom of the FM band on a car radio, over pretty much all of central and eastern North Carolina.

WECT’s digital signal, however, won’t be coming from the old tower. I’m not sure why, but I’m sure it’s just too far away. Instead WECT’s new DTV signal is currently licensed for Channel 44, and transmitting with a directional pattern from the WUNJ (NC Public Television) tower southwest of Wiilmngton. I see by an fccinfo.com query that WECT also has an application for a Channel 44 signal on a higher tower. The site is where WWAY now sits, along with WUNJ (same tower). Since WECT’s bug-splat directional pattern with that application is nearly identical to WWAY’s digital one on Channel 46, along with WSFX’s on Channel 30 — and they all have the same antenna height — I am sure we are looking at a new master antenna for WWAY, WECT and WSFX, with WUNJ broadcasting from a lower antenna on the same 2000-foot tower (which is already standing).

In any case, WECT loses Fayetteville.

Recently, I visited the site of another Channel 6, and put a photo essay up on the Linux Journal Flickr Site. This Channel 6, WLNE-TV, also has an audio signal I can hear in Boston on any radio, even though the transmitter is southeast of Providence, in Rhode Island. The tower is 1000 feet high, and otherwise occupied only by a small Spanish-language FM station. The facility will surely be mothballed while the new digital signal comes from an antenna structure shared with other DTV stations in Providence.

How many more of these huge TV structures will be abandoned in the digital switchover, I wonder? Whatever the number, it will help accelerate the end of TV as We Know it.

Which is my point. This essay, and a shorter one in an upcoming Linux Journal, are swan songs for my expiring expertise (such as it is, or was) in analog broadcast engineering. Knowing this kind of stuff will be as useful to me as the Morse code I haven’t used in close to 50 years. And I’m looking forward to it.

Because the failures of the DTV switchover will bring into sharp relief the obsolescence of official notions about What TV Is.

What we called TV has already become nothing more than a form of data that can be carried over the Net at nearly zero cost, and stored anywhere for about the same. Live transmission is a demanding thing, but not once the pipes get fat enough. Where they aren’t, we have podcasting and variations in file size to avoid bandwidth hoggery.

Already anybody can produce high-def TV. As devices such as the Red camera come down in price, along with processing, data storage and render farming, Hollywood-grade video production quality will no longer be exclusive to Hollywood. Collaboration and distribution over the Net will inevitably follow.

As it does, it will become ever more clear that “TV stations” will be repositioned as doomed mainframes.

There will always be a need for local and regional news, and coverage of events by organizations and individuals whose interest and expertise is also local and regional. But “range” will be determined by interest, not by transmission medium. The lack of capacity for new program sources on one-way cable and satellite systems will expose the antique natures of those systems as well.

For example, the fiber coming to my house has “bandwidth” in excess of a terabyte in both directions, not that it’s sharing much of it. Still, it’s great that Verizon (through FiOS) gives me 20Mb symmetrical bandwidth, but — as Bob Frankston started asking three years ago — Why Settle for Just 1%? More to the point, why settle for TV when you can do anything with video files or streams of any size? Trust me, the time is coming.

At some point, the need for that capacity outruns the need for television. When that happens, vast new markets will open. Including ones far bigger than what we’ve had with TV alone for the last sixty years.

Until then, we’ll just have to imagine them. But don’t worry, they’ll become real soon enough.

Some follow-up:

- Antennas on roofs are all but gone. Best of the few that persist are made (or sold as kits) by the German company Televes. I use this one to pull in signals from Indianapolis, about sixty miles away. Since nobody wants a thing that looks like a fish skeleton strapped to their chimneys anymore, mine is on an 18-foot pole on the side of the house almost nobody sees.

- In a series of “repacks” since this was written, TV stations have moved to a smaller “dial” that ends at channel 36. Every frequency above that has been reallocated or sold, mostly to mobile phone companies. This was a financial windfall for many stations lucky enough to occupy the sold-off channels. Anyway, many stations, including some mentioned above, are on new channels (no matter how they appear on one’s TV—the displayed channel is a virtual one), requiring that viewers “re-scan” to find the channels again. And many of those signals are much weaker or occupy smaller signal footprints.

- The famous WECT/6 2000-foot tower was demolished on September 20, 2012. WECT’s own raw video is gone from the story it posted about the demolition, but YouTube has the whole thing.

- You can now record good 4K video on a smartphone, in stereo.

- I now have a 2 GB/s fiber connection at this house.

Tags: Broadcasting · Television

Who needs humans? Or reality? Meta plans substitutes for both.

Jealous of Amazon’s and Apple’s successes in retail, Meta has created the first completely fake customers to spend money on fake products and services, delivered by fake drivers in fake trucks, all powered by real Meta AI. “We see no reason why the entire economy, from manufacturing and distribution to customers, can’t go entirely virtual,” said Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, speaking to a virtual room filled with virtual reporters taking virtual notes. “We even expect virtual cities to develop, with virtual workers in virtual companies, plus suburbs, farms, and natural wonders that virtual travelers can visit, riding in virtual trains, planes, and cars.” At press time work was halted when virtual developers found that virtual vehicles kept falling off the edge of Meta’s flat virtual world. Also, most virtual agencies for virtual Meta advertisers kept trying to use virtual Meta cash to make Adsense buys in Google world.

Tags: Humor

“All we know is it’s dark down there.”

HALFACAT, Indiana —Local officials remain stumped by a pothole with no apparent bottom on Ferndog Pike, near the intersection with Poady Road. According to Rusty Midfoster, Street Maintenance Supervisor for the city, “We get a lot of potholes here, but most of them are small and hold water, but this one I don’t know. We dropped a cone in it and didn’t hear a splash. Or anything.” At press time, the city’s Special Projects Coordinator and Director of Street Operations were preparing to publish a new QR code to replace the one that replaced the pothole tip line that was replaced by an email address in 2022. It should appear soon at halfacat.in.gov/you-report, where non-emergency forms can be filled out.

Tags: Roads/Bridges · Rural · Traffic & Parking · Travel

October 16th, 2024 · 1 Comment

The red and white “Walnut Grove Tower” or “Transtower” was built for several Sacramento TV stations. It was built in 1961. I took this photo in 2019.

Stainless is folding. This is a matter of quiet but extreme significance for TV and FM broadcasting. This is because, to source the About page on the Stainless website, the company has—

- Constructed over 50% of the tall towers standing in the United States today

- Installed over 50% of the TV broadcast antennas on air during the analog-to-digital conversion (1996-2006)

- Designed and built more 2,000-ft towers than all other companies combined

- Pioneered industry-leading safety and training programs, like NATE STAR and NWSA.

Stainless was already in trouble when its assets were acquired by FDH in 2015. By then all the biggest had already been built, and demand for new ones was between small and nil. The situation is surely far worse now.

Broadcasters everywhere are losing viewing and listening shares to Internet files and streams. Live broadcasting is largely sidelined. Do you still use a radio other than the one in your car? Or at all?

Do you watch over-the-air TV from an antenna? Can you get stations from more than a couple dozen miles away?

TV’s digital transition in 2008 gave us better pictures but worse range for signals. “Repacks” of signals on different channels after spectrum auctions made things worse by forcing viewers to have their TVs re-scan for signals, some of which couldn’t be found. On top of that, all new TVs today come equipped to spy on on viewers, and are designed to discourage watching over-the-air TV. (Our TCL Roku TV now demotes over-the-air station listings to hard-to-find locations amidst hundreds of junk “channels” in its guide.)

To be fair, some over-the-air viewing persists. Consumer Reports says,

…about 20 percent of U.S. households with internet access now use a TV antenna, according to research firm Parks Associates.

That number is likely to rise over the next 12 months, as a new over-the-air standard, called ATSC 3.0 or NextGen TV, rolls out. Right now, these signals are available in about 80 percent of the country. The technology promises greater reliability, higher-quality video with high dynamic range (HDR), better sound, and even some new interactive features, including internet content that’s carried alongside traditional TV broadcasts.

We are one of those households. Here in Bloomington, Indiana, an indoor antenna will only get the PBS station (WTIU/30). Most of the other TV network stations (ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, etc.) come from the antenna farm on the far side of Indianapolis, close to 60 miles away. To get those, I’m going to some trouble to get those signals, from transmitters almost 60 miles away in Indianapolis. For that I built this DAT BOSS MIX LR antenna High-VHF/UHF (Repack Ready) antenna and tested it in the upstairs future bedroom of a house we’re building in Bloomington that happens to enjoy a hillside view in the direction of Indianapolis, which made me optimistic enough about signal prospects to risk spending almost $200 on the antenna. The hard get here was the farthest transmitter: WTHR/13 (which I visited in August). As you can see, I was able to get it, along with all the other full-size stations up there, including the ones that started transmitting ATSC 3.0 signals three years ago:

My home-built TV antenna and a test TV I bought for $35 at a Salvation Army thrift store. For test purposes, it did the job. The antenna will be installed on a pole outside to the right of the sliding doors through which the antenna is looking at Indianapolis.

Still, what you can get on your phone and computer over the Internet has a zillion-to-few advantage over what you can get over the air from broadcast TV and radio stations.

Thirteen years ago, my teenage son asked me what the point of “range” and “coverage” was for radio, when every source was also on the Internet, which you could get nearly everywhere. When I started to explain the point to him, he interrupted me with three words: “Radio is dead.”

So is over-the-air television. It’s a dead tech standing. What’s walking are companies like FDH. And their direction is away.

Tags: Broadcasting

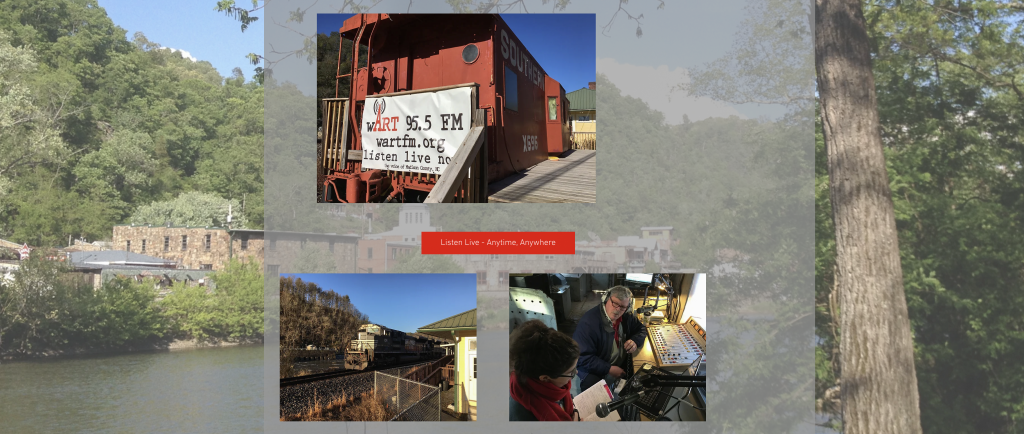

WART radio, along the tracks beside the French Broad River in Marshall, NC.

I heard on iHeart’s wall-to-wall coverage of Western North Carolina’s recovery from Hurricane Helene devastation that the famous (among radio folk) red railroad caboose studios (above) of WART/95.5 FM in Marshall, North Carolina, had been swept away, along with much of the town, which hugs the banks of the French Broad River downstream from Asheville and north of that city.

According to this report by Chris Henning in USA Today, Marshall’s downtown has been severely damaged: “Streets full of thick mud. Mangled debris. Twisted train tracks and overturned vehicles.” (Here’s a video.)

As it turns out, WART transmits from higher ground, from an antenna on the tower hosted by WHBK/1460 and 95.9. Here’s a Google StreetView. Right now WART’s stream is gone (from its app as well, which I just downloaded), though WHBK’s gospel music is on the stream at the WHBK website. (I don’t know if that stream is coming from elsewhere or the station itself.)

I do know that WART is volunteer-powered, much like WFHB here in Bloomington, Indiana.

At times like this, radio is community infrastructure. As a former North Carolinian (1965-1985) and just a concerned human being, I hope to hear word from folks in Marshall about work to restore the town, including its community radio stations.

Tags: Broadcasting · Emergency · Radio

September 30th, 2024 · No Comments

For live reports on recovery from recent Hurricane Helene flooding, your best sources are Blue Ridge Public Radio (WCQS/88.1) and iHeart (WWNC/570 and others above, all carrying the same feed). Three FM signals come from the towers on High Top Mountain, which overlooks Asheville from the west side: 1) WCQS, 2) a translator on 102.1 for WNCW/88.7, and 3) a translator on 97.7 for WKSF/99.9’s HD-2 stream. At this writing, WCQS (of Blue Ridge Public Radio) and the iHeart stations (including WKSF, called Kiss Country) are running almost continuous public service coverage toward rescue and recovery. Hats off to them.

Helene was Western North Carolina‘s Katrina—especially for the counties surrounding Asheville: Buncombe, Mitchell, Henderson, McDowell, Rutherford, Haywood, Yancey, Burke, and some adjacent ones in North Carolina and Tennessee. As with Katrina, the issue wasn’t wind. It was flooding, especially along creeks and rivers. Most notably destructive was the French Broad River, which runs through Asheville. Hundreds of people are among the missing. Countless roads, including interstate and other major highways, are out. Communities have been washed away.

For following what’s happening there, I highly recommend listening to Blue Ridge Public Radio (WCQS/88.1) and any of the local iHeart stations (listed the image above). All of them are carrying the same continuous live coverage, which is excellent. (I’m listening right now to the WWNC/570 stream.)

Of course, there’s lots of information on social media (e.g. BlueSky, Xitter, Threads), but if you want live coverage, radio still does the job. Yes, you need special non-phone equipment to get it when the cell system doesn’t work, but a lot of us still have those things. Enjoy the medium while we still have it.

Item: WWNC just reported that WART/95.5 FM in Marshall, with its studios in a train caboose by the river, is gone (perhaps along with much of the town).

Tags: Uncategorized

A parking meter in Wheeling, West Virginia.

On our drive back to Indiana from New York last week, we stopped for dinner in Wheeling, West Virginia. This was the meter for the space where I parked across from Elle & Jack’s (which I recommend). It’s an old-fashioned mechanical meter, with slots for nickels, dimes, and quarters. All three were plugged. We took an outside table across from the space, where I asked the waitress what the parking hours were. “With all the construction downtown, it doesn’t matter,” she said. “You’re fine.” I suppose that meant the city wasn’t big on enforcement at the time.

But I was prepared to pay because I have a ParkMobile app, which I use here in Bloomington. With some experience at using the app, I’d like to make a couple of points about the shift of parking payment infrastructures from old to new.

First, it’s interesting that this parking meter is now just a sign for ParkMobile. The legacy design pattern had me fooled when I parked because it seemed to welcome coins before I discovered the slots were plugged. Also, the parking meters in Bloomington are a newer kind that are both mechanical and electronic: they accept quarters, while also displaying the ParkMobile zone. Since paying with coins costs less than using the ParkMobile app, we keep a cache of quarters in a little dashboard compartment for that purpose in our new used car (a 2017 VW Golf Alltrack, which I also recommend). But Wheeling made a good cost-saving choice by leaving the meters in place and putting a ParkMobile sign on them.

Second is that ParkMobile still has room to improve. A few weeks ago, I got a parking ticket during the two hours I bought from ParkMobile using the app. When I went to the city parking office to dispute the ticket, they told me the ticket was for my old New York license plate, which was still active on the app, but not the one I selected, which was for the current Indiana plate. ParkMobile should make it easier to delete an old plate and fix whatever went wrong after I selected the right one. I believe this is not an uncommon occurrence, because a conversation I half-overheard at the parking office suggested as much.

I have more thoughts about the transition of parking payment from legacy systems to apps on phones, but I’ll save those until I know more about the topic than I do now.

Tags: Standards · Traffic & Parking · Travel

If you want an idea of how key to Baltimore the Francis Scott Key Bridge is, here are some photos to remind you:

Baltimore Harbor. Note the Francis Scott Key Bridge, above the middle.

On the right is the Francis Scott Key Bridge, also known in its time as the Car Strangled Spanner. It was dropped by the MV Dali container ship. Note that these ships all load and unload on the far side of the bridge at many docking sites. All need to thread the eye of the bridge’s needle.

This view shows the whole span of the bridge, from the north side to the south, across the mouth of the harbor.

Those three are among six I’ve posted on Flickr for the sole purpose of making them useful. Such as now, twelve years after I shot them. Because yesterday an errant cargo ship, the MV Dali, brought the bridge down by taking out the southwest support column (left side in this view) for the central span, killing at least six people and leaving the “Car Strangled Spanner” out of commission for the next few years.

Like all my other public photos, these are Creative Commons licensed to require only attribution. I see this as the infrastructure of public photography supporting the infrastructures of journalism and archivy.*

Photographically, they aren’t great. But they are free, so if you’re writing about the bridge and want an easy photo to use, have at ’em.

*Meaning (if you skip that link) “the discipline of archives.” For the practice of creating and maintaining archives, I prefer archivery, and would have used it here if a search for that word hadn’t suggested archivy instead.

Tags: Building · Emergency · Geography · Industry · Media · Photography · Roads/Bridges · Travel · Water

“American vs. Canadian Radio” — drawn by bing.com/images/create

A couple of years ago I was asked on Quora, “How do American radio stations compare to Canadian stations?” This was my answer.

Mostly the differences are regulatory. But some are also geographic. Examples:

- The Canadian government has a national network, the CBC, much as does the U.K. with the BBC. And, like the BBC, it’s very reputable. Both are “royal” entities, for which there is no U.S. equivalent. (And no, NPR doesn’t qualify, since it’s independent of the federal government and almost entirely—last report, 98+%—paid for by member stations, sponsorships and underwriting.)

- Programming is more highly regulated, especially around music, in Canada. For example, the Canadian Radio-Televsion and Communmicatons Commission (CRTC) has Canadian content requirements for music on Canadian radio, which requires that commercial, community, campus and native radio stations “must ensure that at least 35% of the Popular Music they broadcast each week is Canadian content.” The percentage for CBC stations is 50%.

- The CRTC is committed to sunsetting AM broadcasting, while the FCC is not. While there are still some CBC stations still on the AM band, many signals have either gone dark or have been sold off. Here is a list of the remaining CBC AM signals.

Despite Canada’s slow rollback of AM broadcasting, its prairie features an AM station with the largest daytime* coverage in the world: CBK/540 in Watrous, Saskatchewan. While there are lots of 50,000-watt stations in the world (and that’s the max allowed in the U.S. and Canada)—and a handful cranking out up to two million watts—CBK’s 50,000-watt transmitter sits on some of the most conductive dirt in the world, giving the station coverage that reaches from the Rockies in Alberta to the west, the shores of Hudson Bay to the east; and north across the borders of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and well into Montana, North Dakota, and Minnesota to the south:

One of those two million-watt giants is Transmitter Solt, for Kossuth Rádió, Hungary’s national radio station. While its signal is immense electronically, its daytime* coverage, while very large, is limited by relatively nonconductive ground. Still, in a way, Transmitter Solt is also Canadian, since the transmitter itself is made by Nautel, of Nova Scotia, which in recent years has become what some regard as the preeminent maker of broadcast transmitters.

______________________

*Note that coverage by day and night is vastly different for AM (aka MW) radio. That’s because in daytime the lowest (D) layer of the ionosphere absorbs signals in that band, and at night the same signals bounce off the next layer up (E) for distances typically of several hundred miles. Or, in cases like Transmitter Solt, thousands of miles. As a somewhat separate matter, shortwave signals bounce off the higher F1 and F2 layers. Check that last link for particulars.

Tags: Broadcasting · Geography · Radio