The towers transmitting the directional signals of AM stations WMCA/570 and WNYC/820. Both are aimed toward New York City from a site alongside the east spur of the New Jersey Turnpike.

I’ve been enjoying The Divided Dial, an On the Media NPR series hosted by Katie Thornton. And, as an old radio guy who knows a bit about how radio waves work, I felt the need to share a correction today when I heard Katie say AM waves come from the tops of towers. So I just posted this through her comment form (adding a couple of links):

Hi Katie. Love the Divided Dial series. One small edit: AM signals do not come from the tops of towers. The waves are so long at AM’s low frequencies that the best way to transmit is using whole towers. In older antenna systems (such as the kind on the FCC’s official seal), the antenna is a vertical wire suspended from what’s called a “hammock,” “bedspring” or “clothesline” between the tops of two towers. That was an early approach that used the horizontal wires between the tops of the two towers to extend the electrical length of the vertical wire between them. But once the bases of towers could be insulated from the ground (thanks to advances in ceramics), and building very tall towers became practical, that approach was abandoned. Most AM stations are also directional. Where you see collections of towers of equal height in a row, a triangle, or a grid, those are AM stations. With their much shorter wavelengths (about as long as outstretched arms), FM antennas can be small. And, since signals go not far past the horizon, FM antennas tend to be mounted atop towers, mountains, and tall buildings. Same with TV. For wi-fi and cellular transmission, frequencies are very high, and antennas are small enough to fit inside or on the edges of small and portable devices. Ever notice the lines that seem to have no purpose dividing sections of the edges of your iPhone? Those are insulators between antennas that are also the edges of the phone’s case. Cheers, Doc

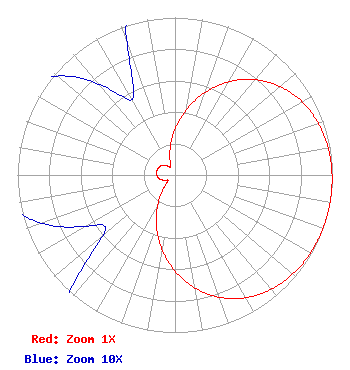

The photo above is from an album I shot when visiting the transmitter site of WMCA and WNYC. The three towers together create directional patterns for both stations. Built by the Truscon Steel Company in 1940, they are some of the oldest broadcasting towers still in use. WMCA’s pattern is the same day and night, and looks like this:

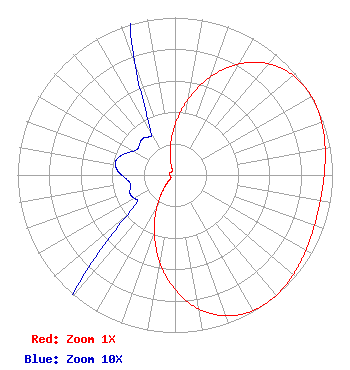

WNYC’s is different day and night, and look like this:

WMCA is 5000 watts full time, and WNYC is 10000 watts by day and 1000 watts by night.

Ground conductivity also affects coverage. The most conductive ground is salt water, and the least conductive is hard bedrock and glacial debris, such as what comprise New York’s boroughs and Long Island. This is why WMCA’s actual coverage looks something like this (courtesy of RadioLocator.com).

That blue line encompasses Bermuda. In its top 40 glory days, WMCA got occasional daytime requests from there. Note that ground conductivity varies a great deal. The best ground conductivity is across sea water, which is why WMCA does so well on the Atlantic and up Long Island Sound. The worst ground conductivity in the US is Long Island, as you can see. It’s also bad across Connecticut and western Massachusetts. In WMCA’s top forty heyday, in the early 1960s, it had daytime listeners in Bermuda, almost 800 miles away. (Not touching nighttime skywave in this post. I’d rather open one can of words at a time.)

Stations with the lowest frequencies on the AM band also have the longest waves, which also travel best along the ground. This is why WNAX, in Yankton, South Dakota, on the same channel as WMCA and also 5000 watts, has daytime coverage that looks like this:

The ground conductivity in prairie states is some of the highest in the country. When my mother was growing up in Napoleon, North Dakota, her family’s favorite local station was WNAX, which was 280 miles away.

The main differences between WMCA and WNAX are ground conductivity and tower length. The ground in prairie states is the most conductive on Earth—technically, 30 mhos/m—while the ground in Long Island is just 0.5 mhos/m. WNAX’s day tower is also unusually tall. At 911 feet, it is more than a half wavelength, making for maximally efficient groundwaves. WMCA’s towers are 336 feet tall: less than a quarter wavelength, and much less efficient.

If we were to invent radio today, we wouldn’t have AM at all. We also might not have FM. Or even radio, since what one might find on a limited number of available signals (from things called “stations”) using a single-purpose device called a “radio” has little audience appeal now that everyone has a phone that can access a zillion sources of information and entertainment anywhere there are cellular or Wi-Fi connections to the Internet.

Still, while radio is still around, it helps to know something about how it works. Hopefully, this post is close to right. I invite corrections. Thanks.

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment