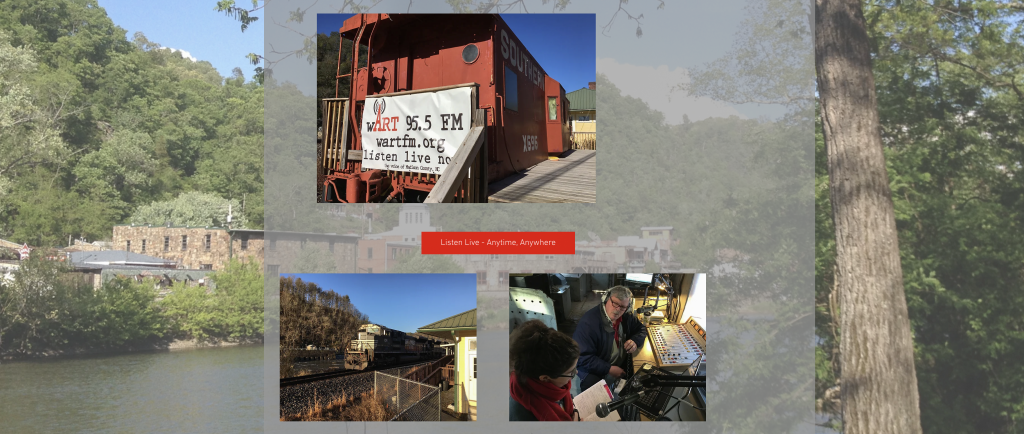

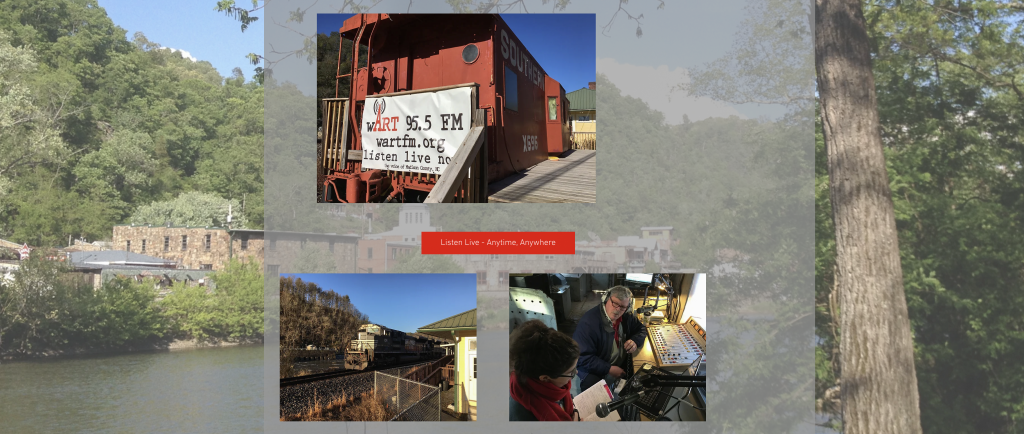

WART radio, along the tracks beside the French Broad River in Marshall, NC.

I heard on iHeart’s wall-to-wall coverage of Western North Carolina’s recovery from Hurricane Helene devastation that the famous (among radio folk) red railroad caboose studios (above) of WART/95.5 FM in Marshall, North Carolina, had been swept away, along with much of the town, which hugs the banks of the French Broad River downstream from Asheville and north of that city.

According to this report by Chris Henning in USA Today, Marshall’s downtown has been severely damaged: “Streets full of thick mud. Mangled debris. Twisted train tracks and overturned vehicles.” (Here’s a video.)

As it turns out, WART transmits from higher ground, from an antenna on the tower hosted by WHBK/1460 and 95.9. Here’s a Google StreetView. Right now WART’s stream is gone (from its app as well, which I just downloaded), though WHBK’s gospel music is on the stream at the WHBK website. (I don’t know if that stream is coming from elsewhere or the station itself.)

I do know that WART is volunteer-powered, much like WFHB here in Bloomington, Indiana.

At times like this, radio is community infrastructure. As a former North Carolinian (1965-1985) and just a concerned human being, I hope to hear word from folks in Marshall about work to restore the town, including its community radio stations.

If you want an idea of how key to Baltimore the Francis Scott Key Bridge is, here are some photos to remind you:

Baltimore Harbor. Note the Francis Scott Key Bridge, above the middle.

On the right is the Francis Scott Key Bridge, also known in its time as the Car Strangled Spanner. It was dropped by the MV Dali container ship. Note that these ships all load and unload on the far side of the bridge at many docking sites. All need to thread the eye of the bridge’s needle.

This view shows the whole span of the bridge, from the north side to the south, across the mouth of the harbor.

Those three are among six I’ve posted on Flickr for the sole purpose of making them useful. Such as now, twelve years after I shot them. Because yesterday an errant cargo ship, the MV Dali, brought the bridge down by taking out the southwest support column (left side in this view) for the central span, killing at least six people and leaving the “Car Strangled Spanner” out of commission for the next few years.

Like all my other public photos, these are Creative Commons licensed to require only attribution. I see this as the infrastructure of public photography supporting the infrastructures of journalism and archivy.*

Photographically, they aren’t great. But they are free, so if you’re writing about the bridge and want an easy photo to use, have at ’em.

*Meaning (if you skip that link) “the discipline of archives.” For the practice of creating and maintaining archives, I prefer archivery, and would have used it here if a search for that word hadn’t suggested archivy instead.

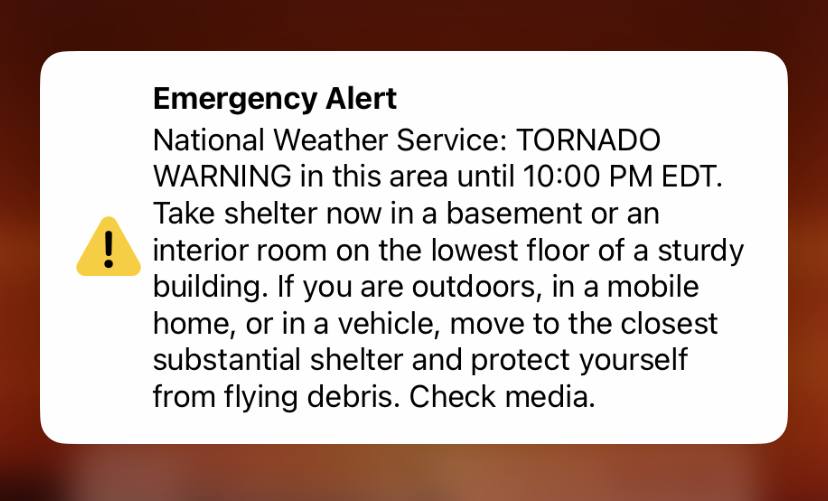

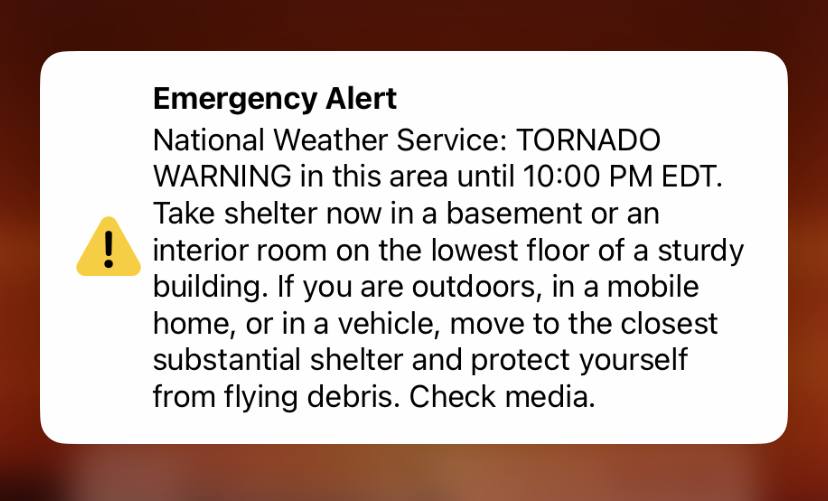

A few months ago, here in Bloomington, Indiana, everyone’s cell phone blasted an emergency warning sound, along with the alert above: a tornado waring. At the same time, civil emergency sirens wailed all over town.

A TORNADO WARNING means a tornado has been spotted or close enough. (A WATCH means there is a risk of a tornado.) Note the last two words: Check media.

That we did, here in the basement where I’m sitting right now. (It’s my office.) First I went to our only local AM station, WGCL/1370 (also 89.7 on FM). On the air was an interview with a guy talking about his tattoos. Then I checked all the local and regional radio stations listed here (on the LocalWiki where I dutifully put them):

Nothing. On any of them. Not even on WFIU, which is the substantial public station at Indiana University.

While I fiddled around with a portable radio, my wife wisely asked, “Have you checked Twitter?” I hadn’t, so I opened a browser on my computer, searched for #Bloomington and #Tornado, and got all the information we needed: everyone was hunkering down, and nobody had seen a tornado. So, we all lucked out.

But the experience was relevant to the regulatory alarms that were being raised, about car makers’ plans to drop AM radio from their cars’ dashboard infotainment systems. For example, Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey’s bill S. 1669: AM Radio for Every Vehicle Act of 2023 seeks required inclusion of AM radios in cars, so IPAWS, the Integrated Public Alert And Warning System “described in section 526 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (6 U.S.C. 321o)” (says the bill) would blast through AM radios, and hopefully save some listeners’ asses.

In a press release, the good Senator said this: “Unlike FM radio, AM radio operates at lower frequencies and longer wavelengths, enabling it to pass through solid objects and travel further than other radio waves.”

Not exactly. AM and FM work differently, but both have limited range, and every station has its own coverage pattern. And none of those equal cellular Internet and satellite radio in overall coverage, though both of those have limitations as well.

[As an aside, not long after I wrote this post, I visited two stations in one studio in Palm Springs, California, and published a photo album of the visit here. Best I can tell, both stations live off rent to cell companies for the tower behind their studios. And they don’t even own the tower anymore. A company that specializes in cell towers and rental owns it, and pays the station owner for the right to occupy the land. From what I saw, neither station was ready to deal with an emergency. Sure, maybe somebody could be called in, but on-site staffing was the exception, not the rule. Oh, and there was a third station once transmitting from the site, but that one was kindly donated to a local college whose staff and students weren’t interested in it, and turned in the license.]

If we were to zero-base radio today, we probably wouldn’t have stations at all. We’d have streams and podcasts, over the Internet, coming from anybody who wants to put out whatever they please. It would all be delivered by fiber, copper wiring, and cellular wireless, perhaps with satellite broadcasting thrown in.

Of course, we have that already.

By the way, Markey’s ploy worked, to some degree. For example, Ford reversed its plans to drop AM radio from its new cars. But AM towers everywhere are being logged off land sold to make room for housing developments and shipping centers. Examples: WMAL in Washington, WFNI in Indianapolis, and WFME in New York—to name a few among many.

Almost all the rest persist on shoestring budgets. You hear programming (now re-dubbed “content”) on their airwaves, but in most stations you will find no human beings sitting in a studio and working a control board with a microphone in their face. Those people got laid off long ago. Nearly all content is piped in from elsewhere. Voices included.

AM also sounds like shit. It doesn’t have to, but it does. For that problem you can mostly blame the radio makers, especially for cars. Switch from FM to AM, and it sounds like somebody just put a pillow over the speakers.

The simple fact is that AM radio is moving toward obsolescence while its popularity drops toward zero. (Ratings on the whole are bad and getting worse.)

Of course, emergency notifications are important. The question of how best to blast out those notifications and then get good news coverage during and after an emergency can be answered in lots of ways. But keeping AM stations running may not be the best of those options.